In the course of PACE’s 2013 winter session, 23 January, on the one hand, could be described as a day of Azerbaijan, on the other hand, as a day for parliamentarians of the Council of Europe for passing the test of supremacy and impartiality of laws with dignity.

On that day, two important reports on Azerbaijan were simultaneously tabled for discussions at the plenary session of the Assembly. One of them was a report on “The honoring of obligations and commitments by Azerbaijan” by Pedro Agramunt (EPP) and Joseph Debono Grech (SOC), the co-rapporteurs of the PACE Monitoring Committee. The second was a report on “The follow-up to the issue of the political prisoners in Azerbaijan” by Christoph Strâsser (SOC), the rapporteur of the PACE Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights.

The report by the co-rapporteurs, Pedro Agramunt and Debono Grech, underlined that “the Monitoring Committee recognizes the progress made by Azerbaijan with regard to the establishment of the legislative framework in some areas crucial for the functioning of democratic institutions since its accession to the Council of Europe; at the same time, it encouraged the Azerbaijani government to make strides in enforcing the legislation in these spheres.”

The report underscored the strategic significance of the “secular and multi-religious” Azerbaijani society and credited the Azerbaijani government for the “pro-European commitments” and for managing to “keep away the Islamic fundamentalism” and for pursuing “the policy of integration into Euro-Atlantic

structures”.

The lion’s share of the report that mentioned the “occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh and seven surrounding districts with a total of up to 20% of the Azerbaijani territories” was devoted to the Nagorno-Karabakh war.

The report regretted that “900,000 people, or 10% of the country’s population, are internally displaced persons (IDPs) and they remain a heavy burden on the political and social state of Azerbaijan” and that “Armenia’s reluctance to cooperate hinders thead-hoc committee”.

The report covered a whole range of issues, starting from economic and social issues, free and fair elections, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and association.

Over 20 items of the report discussed the issue of political prisoners. A list of 22 political prisoners, as alleged by international NGOs at that time (21 of them were released under the latest presidential acts of pardon) was looked into by the report.

In general, the report of the Monitoring Committee was a balanced and comprehensive document. Thus, the co-rapporteurs made numerous fact-finding visits to Azerbaijan within the framework of their competencies. During their visits, the co-rapporteurs held meetings with the opposition, the government, NGOs, as well as with the dvil society representatives.

They cooperated with representatives of the Azerbaijani government, the opposition, as well as with the civil society sector representatives in an effort to unbiasedly assess any issue that emerged. Consequently, the report prepared by the co-rapporteurs was assessed as a balanced document.

However, the same opinion could hardly be said about the report of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights. Thus, after being appointed as the rapporteur of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights, Christoph Strässer decided to exert pressure on the Azerbaijani government and politicize the issue, instead of establishing cooperation with the Azerbaijani government, as well as with different actors in society. Azerbaijan twice sent an invitation letter to Christoph Strässer, inviting him to visit the country.

Under various pretexts, within his rapporteur mandate, he had never paid visits to our country. When it turned out that he is reluctant to visit Azerbaijan, a letter was sent to the Secretariat of the Committee to inform that an official of the Azerbaijani Presidential Administration was ready to meet with Christoph Strässer in Strasbourg.

However, Christoph Strässer did not also take advantage ofthis opportunity and went on politicizing the issue, started a political campaign against Azerbaijan by making false claims that he was refused a visa. Moreover, contradictory discussions were being held at the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights when Christoph Strässer was the rapporteur. Christoph Strässer was refusing to carry out inclusive and detailed researches in all member states. He was personally insisting on isolating Azerbaijan. From this point of view, there emerged questions about his impartiality and neutrality.

For this reason, the discussion of Christoph Strässer’s report at the 26 June 2012 meeting of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights proceeded in a tense atmosphere. This tension reached its peak during the PACE’s winter session. Christoph Strässer’s report focused only on the issue of political prisoners. A single list of 85 alleged political prisoners was attached to the report. The rapporteur did not update the list, though he himself admitted that some of the convicts had been released. Heated discussions were underway on both reports at the plenary session of the Assembly. Many MPs were praising the report of the Monitoring Committee, while focusing on the drawbacks in the report of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights.

British MP Robert Walter, leader of the European Democrats Group (EDG), announced that his group would reject Christoph Strässer’s report. MP Catherine Werner from Germany, leader of the Unified European Left Group (UEL), said she would abstain. The European People’s Party (EPP) chose free voting. Only the leader of the European Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), Anne Brasseur, said that her group would unanimously support the report of the Monitoring Committee.

Simultaneously, she added that the majority of the Group was in favor of Christoph Strässer’s report. In fact, Anne Brasseur tried to hold indicative voting regarding Christoph Strässer’s report in the ALDE Group beforehand, and as a result, it turned out that 11 liberals were for the report and 9 were against it. During the discussion, it appeared that almost all liberals, who took the floor, called for rejecting the report. In the end, the Socialists resolutely called to support their leftist colleague Christoph Strässer.

The criticism, pro-and-anti arguments of anti-Azerbaijani MPs, like Viola von Cramon-Taubadel (Germany, SOC), Liz Kristofferson (Norway, SOC), Michael McNamara (Ireland, SOC), Marina Schuster (Germany, ALDE), as well as members of the Armenian delegation on both reports were quickly and fully analyzed and responded by responsible MPs.

Though a number of MPs noted that they faced irrational situation because of the contradictory messages the two different reports on the same topic carried, they underlined that their duty as politicians was to vote rationally using their own judgements.

Although the report of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights carried a list of 85 political prisoners, a number of MPs underlined that the report of the Monitoring Committee contained names of only 22 political prisoners and asked which figures were correct and to what extent they were reliable and up-to-date. Recalling that 75 political prisoners were recently pardoned, some MPs underlined that many on Christoph Strässer’s list was already out of jail. Parliamentarians asked to clarify who were in prison at the moment and wanted to be sure that all those persons, who had been jailed, were only for “political” reasons.

The MPs also noticed contradictions between the reports by Christoph Strässer and by the co-apporteurs of the Monitoring Committee. Several MPs recalled that the co-rapporteurs of the Monitoring Committee had prepared their report, relying on their fact-finding visits to Azerbaijan, as well as the information obtained from various international and local NGOs.

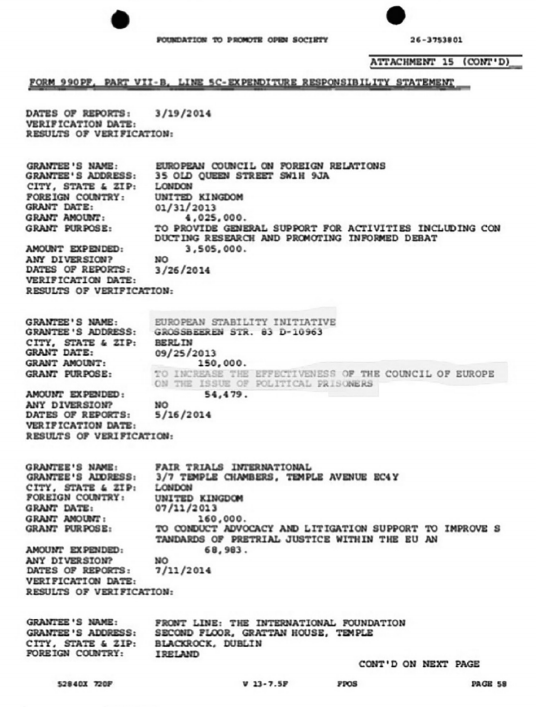

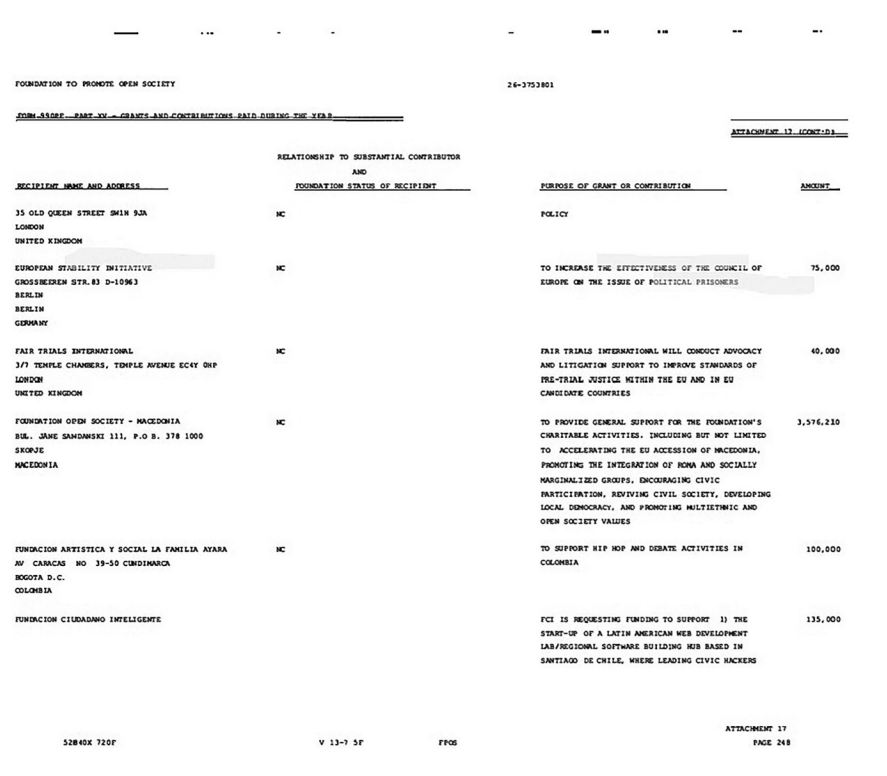

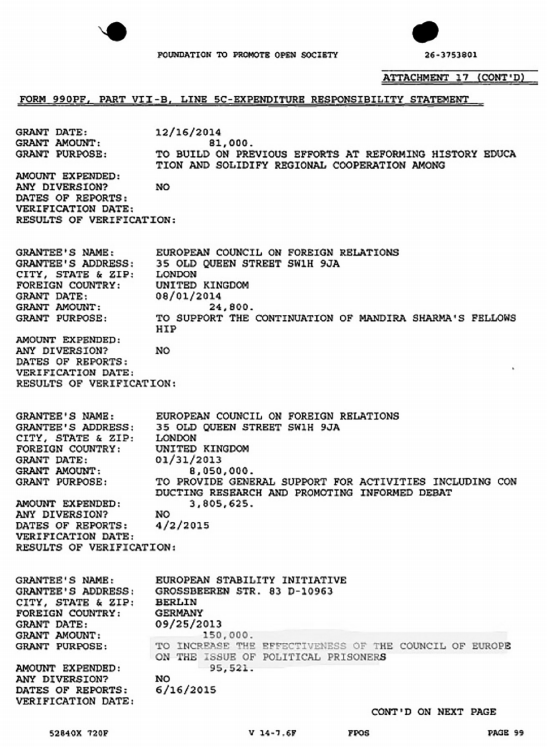

Some MPs complained that the report of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights was based on information two Azerbaijani human rights champions gave him in Berlin. They accused Christoph Strässer of jumping to a conclusion based on information obtained from far away without visiting the country and inability to see the reality comprehensively and effectively.

MPs drew a conclusion that two contradictory reports could not be approved on the same day as they were not only confusing, but would also show the Assembly in a bad light. Considering the importance of the Monitoring Committee’s report for the Assembly as it was more comprehensive and precise report and contained the exact names and the number of the political prisoners in 20 items, a number of MPs approved the report of the Monitoring Group and decided to vote against the report by the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights.

Some MPs complained about difficulties in realizing the work distribution at the Assembly. They noted that the activities of the Monitoring Committee were to monitor the human rights situation only in a member state, that is, in Azerbaijan, adding that the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights was also tasked with the same issue.

MPs said it would lead to false conclusions that the Monitoring Committee was incapable of fulfilling its duties and called on their colleagues to be attentive. They drew attention to the risk of parallel systems that may overlap and replicate each other’s functions.

As to the special country under the monitoring procedure, many MPs noted that it was senseless to prepare additional separate reports on the issue that was envisaged comprehensively in two items (7.1 and 7.2) of the report of the Monitoring Committee. They also called for and supported the idea of preparing a comparative legal report on the issue of the “political prisoners”.

Some MPs went to even greater extremes and accused Christoph Strässer of dual approaches, as he was not willing to include other countries into memorandum on the alleged issue of political prisoner, saying that those countries were under the monitoring procedure.

Some MPs said that an addendum to the report on “the merged list of the presumed political prisoners” as well as a list closed for discussions and amendments of other MPs were inaccurate.

They underlined that even Christoph Strässer “had accepted that many of the presumed political prisoners on the single list were released on different grounds” (item 11). Later they criticized Christoph Strässer for the failure to draw up an exact list of the prisoners in prison at present.

They concluded that he deliberately wanted to bring into disrepute the country he was named the rapporteur. MPs said that the PACE rapporteur’s false statements were out of synch with reality, adding that they both undermined Azerbaijan’s reputation and the credibility of the Council of Europe.

The reason why several MPs did not vote was that Christoph Strässer’s report was directly interfering in the key mission of the Monitoring Committee. They noted that the report of the Monitoring Committee was a priority for them. It was said that the alleged issue of political prisoners should be monitored regularly and continuously, and this was merely the methodology of the procedure of the Monitoring Committee.

A group of MPs expressed their concern over the interference in a mission of the European Court of Human Rights by referring to the wording in items 16 and 37 of Christoph Strässer’s report that “No doubt that, a precedent interpretation of the Convention is the exclusive right of the European Court of Human Rights” and “I am aware that this Assembly is not the court of law. Therefore, I will not reach a final conclusion on the issue of the alleged political prisoners brought to my attention”.

However, on individual cases, he jumped to dozens of conclusions and did vice versa:

-“I decided to include these people in the list of the political prisoners” (Paragraph 36)

-“I consider Mr. Samadov as a political prisoner.” (Paragraph 104)

-“I believe that Mr. Dadashbayli and other members of the group are considered to be alleged political prisoners”. (Paragraph 117)

-“I consider Mr. Farhad Aliyev as presumed political prisoner in accordance with our criteria.” (Paragraph 143)

-“In my opinion, Mr. Rafig Aliyev is also considered to be a political prisoner…” (Paragraph 145)

-“However, I am sure that he can be recognized as a political prisoner by using the same criteria” (Paragraph 146).

Taking into consideration a statement in Christoph Strässer’s report, MPs got the impression that he was at odds with Azerbaijani government officials: (Paragraph 197): “…after they failed to collaborate with me, I am not sure that the current Azerbaijani leadership has a political will.”

Some MPs reminded him that it was exactly his task to establish constructive working relations based on mutual trust with the member state where he worked as the rapporteur in order to prepare a fair, unbiased, objective and impartial report based on facts rather than assumptions.

Parliamentarians, unable to realize his problematic relationship with Baku prior to undertaking his mission, expressed their disappointment over Christoph Strässer’s failure to get in touch with all the sides before making judgments.

Further, they expressed disappointment with Christoph Strässer’s offensive and threatening tone, as well as with the hostile position against Azerbaijan as reflected in paragraph 37 of his report: “The bodies of Azerbaijani government were not able to deliver the real alternative version of the alleged facts during the period of preparation of the report and now they should act as a part of the follow-up to the issue in order not to be held responsible.”

Some speakers said that the role of the Assembly in member states, especially in young democracies, is to promote reforms in the sphere of human rights. In order to increase the level of democracy in those countries, this process should be constructive and pleasant rather than threatening or isolating.

The speakers drew attention to the fact that Christoph Strässer’s report did not focus on comprehensive and precise analyses but mainly the rapporteur’s personal hopelessness. They said that Christoph Strässer turned the report into a battleground between himself and Azerbaijan – a member state, and this unhealthy situation has been marred with obvious biased feelings.

The parliamentarians warned the rapporteur against direct interference with procedures of the European Court. They urged their colleague to be careful since the approval of the report would boil down to the fact that these conclusions were not a position of the rapporteur, that is, of an individual but of PACE’s official and public position.

For instance, Mr. Alexander Sidyakin (Russian Federation) said that the 89/89 result of the voting was very disputable – if an MP did not leave the meeting for a cup of coffee, the definition would not be adopted at the Assembly. He said that everybody should be engaged in own work and if Montesquieu saw one country dictating another country, he would turn in his grave.

Numerous MPs expressed their concern about big differences between the two lists proposed by the rapporteurs of the committees on monitoring and legal affairs on the alleged political prisoners; they warned that it would lead to contradictory results on the same issue, in case both reports were adopted.

Liberal MP Meritxell Mateu Pi from Andorra said that she did not understand why the Assembly was discussing the second report that caused a great commotion in the battle of the figures. Asking “who can deny the existence of political prisoners in other countries of the Council of Europe?” and “Why only Azerbaijan?” Meritxell Mateu Pi put a question to the rapporteur, saying that “political prisoners are everywhere, even in Western Europe, according to Christoph Strässer’s definition. We should monitor the issue of political prisoners in all member states. Otherwise, depending on power and influence of a country in question, we would apply double standards”.

British MP Robert Walter added that “Christoph Strässer’s list did not overlap with the figures of Amnesty International, which visited prisoners in Azerbaijan, or OSCE figures.

Unfortunately, the rapporteur of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights did not pay a visit to the country.” Walter insisted that “the report of the Monitoring Committee rejected Christoph Strässer’s confusing report and its attachment”.

British MP Mike Hancock of ALDE Group referred to the report of Human Rights Watch that shed light on the problem of political prisoners in 13 member states. He suggested that reports should be drawn up for all those countries.

Mike Hancock added that “a member state was targeted. The approach cannot be fair and honest and this cannot be turned a blind eye at the Assembly.” To recap, he said that “the Council of Europe is a serious institution and the rapporteur of this organization should be capable of getting to the bottom of the truth when dealing with such sensitive issues. I cannot undersign such biased and individual statements without profound arguments; so I am not going to endorse your report.”

Some parliamentarians drew attention to the peculiarities in Christoph Strässer’s report, including persons convicted for non-political crimes, such as the premeditated assassination of a prosecutor (Paragraph 178). They added that although independent experts did not consider such cases “political”, nevertheless Christoph Strässer’s personal feeling and consideration rejected thoughts of the experts “who are concerned for the negligence of such opinions”. Incapable of assessing the results of the indepen dent experts with bigger resources to deeply verify these issues, Christoph Strässer added all six persons to his list made up of 85 people.”

Some people were surprised at finding out that views of indeendent experts were not seriously taken into consideration by the rapporteur. However, this encouraged Christoph Strässer to prepare his report and substantiate the main part of his investigation on the results of those three people.

MP Agustin Conde (EPP, Spain) expressed his concern about the persons who were not recognized as political prisoners by independent experts, as well as non-political crimes such as a premeditated assassination included in Christoph Strässer’s list.

“According to the report we adopted in 2012, a murderer or a terrorist can never be considered a political prisoner,” Spanish MP reminded again. “This is absolutely unacceptable. If anybody premeditatedly assassinates a prosecutor in my country, he can never hide himself under the guise of a political prisoner.”

MP Agustin Conde also said that he found hard to understand “why Christoph Strässer was concerned about the non-recognition of the detained three persons as political prisoners”. Numerous MPs drew attention to Christoph Strässer’s dangerous messages on the Islamic extremism.

Nessa Pasquale (EPP, Italy) said that Christoph Strässer wanted members of the extremist groups, detained for plotting to form a Shari’ah state, be immediately released. This approach would undermine many rights protected by the European Convention on Human Rights. MP Nessa Pasquale referred to Article 17 of the Convention, which indicates that every country has the right to protect its constitutional order from the groups wishing to overthrow it.

“Kalashnikov assault rifles, hand grenades and ammunition were found on these people. Isn’t it dangerous to create conditions for the propagation of fundamentalism in the already complicated region?” Italian MP asked, underlining the latest events occurring in a number of countries.

Thierry Mariani (EPP, France) joined his colleague and added: “We should take into consideration that Iran is a large neighboring country of Azerbaijan and finances a political party, as well as a TV channel in Azerbaijan.” He also noted that rights of women are fully protected in Azerbaijan and condemned the efforts to pin labels on the country.

In addition, Thierry Mariani criticized Christoph Strässer for not obtaining a visa to visit Azerbaijan though the rapporteurs of the Monitoring Committee can fulfil their fact-finding missions without any problem.

Theodora Bakoyannis (EPP, Greece) warned against the danger of classifying terrorists as political prisoners. She said that “under the dictatorship in Greece, like my father, I was also a political prisoner when I was 14 years old. The terrorists murdered my friend. There were three murderers, but 10 executors. The first committed the crime, the second took a decision. Now, they want to be called political prisoners and this is unacceptable”.

She said that “if we continue cooperation, we could release people by keeping them under our sphere of influence”. Therefore, I will vote for Pedro Agramunt’s report and be against Christoph Strässer’s.”

Tugrul Turke§ (Turkey) said that Christoph Strässer’s report contained factual mistakes with names of people at large, murderers, and terrorists and even non-existing persons. He alsogave an example of a presumed political prisoner who was convicted for attacking an underground station, killing 14, wounding 20 people, including children.

Terry Leyden (ALDE, Ireland) called for continuing the monitoring process, saying that Christoph Strässer’s parallel report undervalues that of the Monitoring Committee. “I will vote for the report of the Monitoring Committee, as Christoph Strässer’s report is imprecise,” he noted. “We should also take into account that the former Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan has been through a long way and we should believe in the achievements made by this country so far.”

Alexey Ivanovich Aleksandrov (EDG) noted that “Russia assessed these subjective lists as senseless as they damaged the role of the law-enforcement agencies”.

Christoph Strässer was hying to defend his report as a supplement to the continuous research-based report of the Monitoring Committee. However, these arguments, as well as his disappointment were too weak to save his report. Making his last notes, rapporteur Debono Grech said that he knew what a political prisoner was, as he was a captive of the British government 40 years ago. Agramunt underlined Azerbaijan’s geopolitical significance, as well as its importance in the energy supply of Europe.

With regard to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the MP said: “My Armenian colleague Davut Harutyunyan (EDG) said that only 13% of Azerbaijani territories had been occupied not 20%and the number of the internally displaced persons is 900,000 not 1 million. It does not matter how many percent it is. The only problem is that the territories are still under occupation.”

In fact, four parliamentarians from the Armenian delegation were very active during the debates and repeatedly took the floor to criticize human rights situation in Azerbaijan. Interestingly, in the same vein, they were interfering in domestic affairs of neighboring independent states. At least, two Armenian MPs were trying to prove that Azerbaijan was using Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as an excuse to cover up the problems pertaining to human rights issues.

Upon hearing such hostile remarks, everybody could feel seriousness of the problematic relations between Azerbaijan and Armenia that cause major obstacle for security and peace in the Caucasus region. At the same time, Armenian MPs were rejecting the fact that the Armenian aggression caused 1 million people to become internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Azerbaijan.

Nevertheless, the majority of MPs once again felt certain that the allegations about human rights violations in Azerbaijan was a drop in the ocean as against the enormous negative impact of the occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh and other territories by Armenia which led to the violation of human rights, as well as the emergence of 1 million internally displaced persons.

With regard to the issue of the political prisoners, Agramunt underlined that “21 out of 22 political prisoners on his list had been released and there remained only one political prisoner in Azerbaijan”, announcing that he rejected Christoph Strässer’s report as it contradicted to that of his.

The result of the voting was too outright. The report of the Monitoring Committee was adopted with a big majority, 196 votes for and 13 votes against. However, the report of the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights by Christoph Strässer was overwhelmingly rejected with 125 votes against and 79 votes for.

Thus, this was a consensus support for the report of the Monitoring Committee and the expression of trust in two co-rapporteurs. A little bit earlier, some NGOs severely criticized both co-rapporteurs, and even demanded their resignation.

However, by expressing great support to the co-rapporteurs of the Monitoring Committee, 196 out of 225 representatives of the population of the European countries proved that their mandates were not completely controversial.

Unequivocal rejection of Christoph Strässer’s report by the Assembly was a triumph of justice and unbiasedness as well as of human rights and the rule of law in Europe.

Exactly, on this issue, Azerbaijan had been subjected to double standards at international organizations for many years and 23 January 2013 gave hopes that such biased attitudes would be ended. However, further developments of the events showedthat those hopes were in vain…

Silahlı Qüvvələr Günü münasibətilə Xankəndidə hərbçilərin yürüşü keçirilib VİDEO

Silahlı Qüvvələr Günü münasibətilə Xankəndidə hərbçilərin yürüşü keçirilib VİDEO Böyük Qayıdış: Ağdam rayonunun Kəngərli kəndinə növbəti köç karvanı yola salınıb VIDEO

Böyük Qayıdış: Ağdam rayonunun Kəngərli kəndinə növbəti köç karvanı yola salınıb VIDEO Prezident İlham Əliyev Dövlət Gömrük Komitəsinin yeni inzibati binasının açılışında iştirak edib VİDEO

Prezident İlham Əliyev Dövlət Gömrük Komitəsinin yeni inzibati binasının açılışında iştirak edib VİDEO Azad, abad Ağalı kəndimiz…

Azad, abad Ağalı kəndimiz… Budapeştdə Azərbaycan Prezidenti İlham Əliyevin Macarıstanın Baş naziri ilə geniş tərkibdə görüşü olub VİDEO

Budapeştdə Azərbaycan Prezidenti İlham Əliyevin Macarıstanın Baş naziri ilə geniş tərkibdə görüşü olub VİDEO