Palm to palm, we sat and listened as her mother spoke, bearing witness to a narrative both familiar and new. A young woman, woken from her home in the middle of the night, forced to march through the icy woods with no idea where she was going. Wandering into a terrifying darkness with no end in sight. Pummeled by bullets, ripped apart from her family, forced to play dead.

She survived to find herself the sole female prisoner in a camp surrounded by barbed wire. She suffered torture and starvation and rape. She hadn’t uttered a word about it for 23 years.

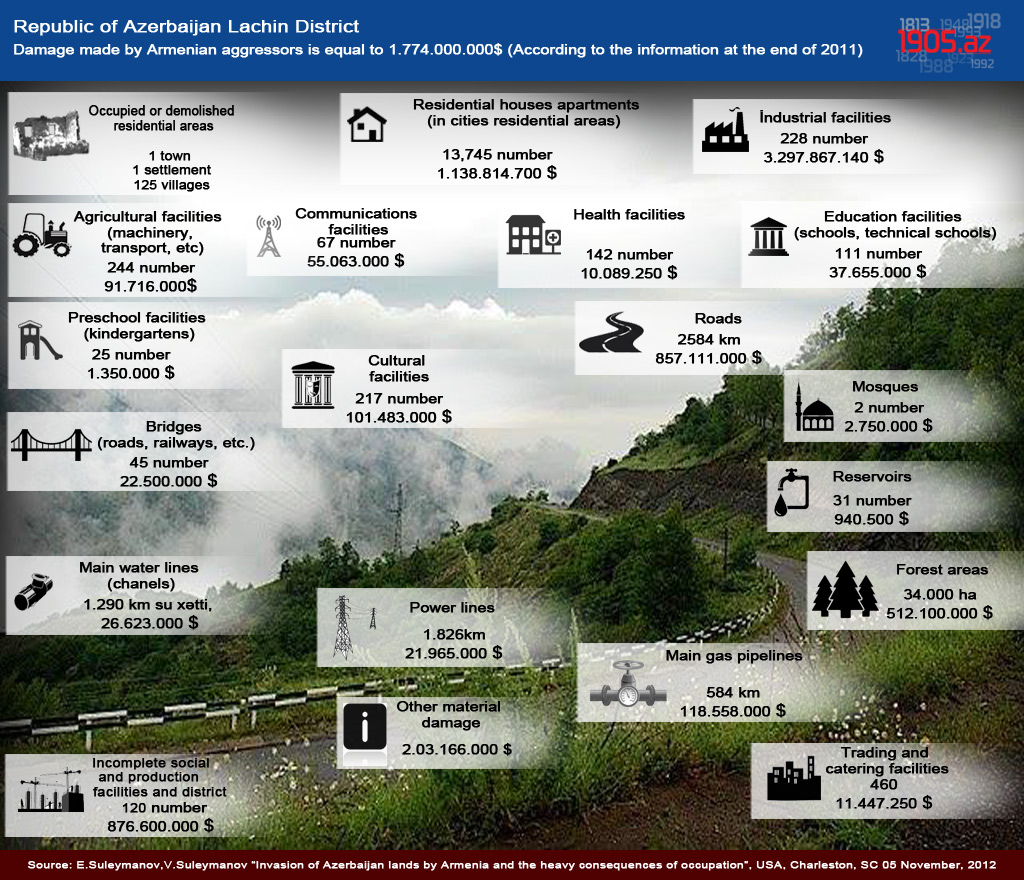

Her nightmare could have taken place in Warszaw, Phnom Penh or Kigali. But it happened in Khojaly, less than a quarter of a century ago. It happened in an unheralded conflict perpetrated by Armenians against the Azerbaijani people, in a place that does not grab headlines or 24-hour news coverage. And until that February evening, I had never known of the pain that screams from the earth in that small village in the mountains of Caucasia.

This was the story of Durdane Aghayeva. I met her in a dear friend’s living room along with other American Jewish women. We had gathered to hear Durdane’s story, to bear witness to her pain, to connect with her resilience. We, too, had tragedy in our bones. Granddaughters of Holocaust survivors, nieces and cousins of too many victims to name, we understood the residual trauma of genocide and connected with the power of storytelling.

But our families had been fortunate, in a way. Our stories have become part of popular consciousness. There are institutions, museums and foundations dedicated to our ancestors’ memories. The world acknowledges and embraces our story; films that tell the tragedy of our people have won Oscars and our history is required reading in schools.

But Durdane was just sharing her story for the first time. A Muslim woman from Azerbaijan, speaking to very Western twenty-somethings. And yet despite any potential religious, cultural or language barriers, the horror of her experience and the humanity of her perseverance united us. We were a group of women drawn together by a shared sense of purpose, paying tribute to a tragedy that transcends all words and encompasses all pain.

As I listened, I connected with Durdane’s 12-year-old daughter. She had accompanied her mother on this whirlwind trip to bring light to the darkness that she had held silent for so long. I recalled my 12-year-old self, and I couldn’t imagine what this sweet girl was processing. I couldn’t comprehend the pain and the sadness that had tinged her life — and now had a voice. So I held her hand, and sat still, and listened.

Listening to Durdane, I mourned how often the deepest pain in our world goes unnoticed. And when rape, trafficking, genocide and massacre remain silent, they become shrouded in shame. But the darkness must come to light before anyone can dream of a future free of these affronts to humanity.

With her daughter’s hand in mine, I prayed that Durdane’s experience would emerge from the abyss of silence. I prayed that her story could bring peace and acknowledgement to the memories of all those she had lost on that cold February night in 1992. I prayed that her brave, fearless sense of self and willingness to share her story would resonate past our circle of women; that the story of Durdane’s survival would bring light to the countless stories that remain untold; that the world would soon recognize and mourn and honor those lost in the massacre at Khojaly.

More than anything, as I held her daughter’s hand I prayed that the bones of the innocent victims would no longer scream silently from the woods outside Khojaly.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/annie-lascoe/bearing-witness_b_7295340.html

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO

Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO

Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO