Armenians gain privileges in Baku’s oil industry

The rapid development of the oil industry in Baku in the late 19th and early 20th centuries attracted a wave of Armenian migration to the city. The Christian Armenians were obedient subjects of the Russian Empire, so the imperial government used them as a tool in their Eastern policy. The Armenians were, therefore, able to gain privileges from the government in Balm’s oil industry and soon became the major entrepreneurs in Baku oil. Armenians dominated the industry to such an extent that they were able to dictate their will to the Congress of Baku Oil Entrepreneurs.

Alongside the industrial elite, poorer Armenians flocked to Baku to find work in the oil fields. As one of the main industrial centers in Tsarist Russia, Baku saw the emergence of an industrial proletariat and revolutionary fervor. Armenian workers, whose number increased considerably in the early 20th century, were active in Baku’s revolutionary and socialist movements.

On the eve of the first Russian revolution, the Armenian nationalist Dashnaktsutsun Party started to spread socialist ideas among Armenian oil workers.

Bolshevik revolution brings chaos and terror

The Dashnaks and other Armenian nationalist parties took advantage of the disintegration of the Russian Empire, when the Tsarist government was overthrown in the revolution of February 1918, and of the Bolshevik seizure of power in the October Revolution. They used the harsh, revolutionary ideas to promote their nationalist agenda.

In 1918-20, Armenians perpetrated massacres, violence and terror against Azerbaijanis in Baku and throughout the Caucasus, plundering their property. They started in Baku in 1905. The massacre of 1918 was prepared more skillfully and implemented more ruthlessly than the 1905 attacks. The Bolsheviks’ victory in Russia and the withdrawal of Russian troops from the battlefields of World War I opened the way for the massacre.

Lenin appointed Stephan Shaumyan commissar of the Transcaucasus.

Shaumyan was a Baku Armenian and Dashnak masquerading as a Bolshevik. When Shaumyan’s attempt to implement his mandate in Tbilisi failed, he returned to Baku. He seized absolute power in Baku – an international proletarian city after the collapse of the Russian Empire – and used his position to fight the Azerbaijanis. Shaumyan took advantage of Armenian officers and soldiers amongst the Russian troops who were returning from the front to Azerbaijan and used them in his anti-Azerbaijani campaign.

Armenian nationalists try to provoke Azerbaijani uprising

The Azerbaijani Democratic Republic set up an Extraordinary Investigation Commission to look into the March killings and charted the following events in the buildup to the massacre. (Under the Gregorian calendar, the massacre occurred from 31 March to 2 April 1918, but under the Julian calendar, in use in the former Russian Empire at the time, the date of the killings is 19 to 21 March 1918. This article uses the modem Gregorian dates.)

In early January 1918 the headquarters of the Muslim troops, organized and led by General M. K. Talishinsky, came to Baku. Armenian Bolsheviks then arrested most of the members of the Muslim corps general staff.

Taking advantage of the arrest of the Muslim soldiers, the Armenians tried to provoke the Azerbaijanis to rise up against the Bolsheviks and Armenians. However, the Azerbaijanis did not succumb to this provocation. As the Azerbaijanis did not rise up, Armenian soldiers began to use violence against them and murdered women, the elderly and children.

According to Christian clergymen who attended meetings in the Baku mosques, all the Muslim clergymen urged Azerbaijanis to remain calm in the face of difficulties and violence. The report said that the Azerbaijanis used every opportunity to find reconciliation. Azerbaijani representatives repeatedly attempted to form an alliance with the Armenians against the Bolsheviks, but the Armenians would not commit themselves.

On 30 March 1918, Armenian Bolsheviks killed most of a division of Muslim troops who were accompanying the remains of Mammed Tagiyev, son of oil baron Zeynalabdin Tagiyev, by boat from Lenkoran to Baku. Armenian Bolsheviks demanded that the Muslim division surrender their weapons and, when the division refused, the boat was shelled.

The next day Armenian soldiers appeared in the Armenian-populated part of the city. In the streets, they started to dig trenches and build barricades with stones and earth.

The commission’s report says that the same day Azerbaijanis met in the Ismailliye, the building of the Muslim Charitable Society. Haik Ter-Mikaelyan, a former Baku officer, attended the meeting and declared on behalf of the Armenian Council and the Dashnaksutyun Party that if the Azerbaijanis opposed the Bolsheviks, the Armenians would help to oust them from Baku.

Carnage

Early the next day, 1 April, while the Azerbaijanis were still asleep, the Armenians attacked them. At first, the Azerbaijanis could not understand what was going on, that Armenian soldiers were attacking them. At Armenian instigation, ships in Baku Bay started to shell the Azeri-populated part of the city. The Armenians had convinced the Russian sailors that the Azerbaijanis were slaughtering Russians in the city. When the sailors found out that the Azerbaijanis had not touched the Russians, they stopped shelling. On the eve of the attack all, the Armenians in the Azeri-populated part of the city had moved to the Armenian side.

Well-trained and well-armed Armenian soldiers attacked Azerbaijani houses in the city’s Azeri-populated areas such as Mammadli and Zibilli. An eyewitness told the special investigation commission: “They were devastating only the Muslim-populated districts, killing the inhabitants, stabbing and bayoneting them, burning their houses, throwing the children into the fire and bayoneting three- or four-day-old babies.” The commission’s report says that the eyewitnesses could not stop crying when they talked about the massacres. Armenians killed Azerbaijanis and then set fire to their houses. The bodies of Azerbaijani women were thrown into pits. Long afterwards, the bodies of 57 Muslim women were dug up. Their ears and sex organs had been cut off and they had been bayoneted in the abdomen. Eyewitnesses said that Armenians beat women with sticks, cut off their hair and drove them out into the streets unveiled and barefoot. The report said that the commission had difficulty in identifying the number of murdered Azerbaijanis, because the Armenians killed entire families in most of the houses and there was nobody left to give the names of the dead.

In another Azerbaijani quarter, Armenian soldiers broke into and looted Azerbaijani houses, brutally killing their inhabitants. They respected neither sex nor age. For example, 80-year-old Haji Amir Aliyev was killed in his own home, alongside his wives who were 60 and 70 years old. Three teenagers were stabbed and his 25-year-old daughter-in-law was nailed alive to the wall.

The Armenian intelligentsia led Armenian soldiers in an attack along Nikolay Street (now Istiqlal). One of the gangs broke into a house where they murdered eight women and children.

Another group in Persian Street broke into the house of Bala Ahmed Mukhtarov, took nine Azerbaijani intellectuals out to Church Square and shot them. Armenians threw two of the corpses into the blazing Dagestan hotel.

The Armenians tried to stir up sailors and Red Guards against the Azerbaijanis too. For example, in the morning of 1 April the Iranian consul and White Russian naval officer Natonson told Azerbaijani representatives in the Old City that Azerbaijanis had killed Russians and Armenians there. In response, the Azerbaijanis took them to the house of Mir Ali Nagi Husseinov where 240 Christians – men, women and children including Armenians – were sheltering. When they saw this attitude toward the Christians, they left the Old City. They came back three hours later and said that two members of the Armenian community had claimed that Azerbaijanis had murdered all the Christians in the Old City. Natonson was sure that they were being deceived by the Armenians and left 20 sailors in the Old City to protect the Azerbaijanis.

Armenians stopped the massacre after the 36th Turkistan regiment issued an ultimatum. The entire Russian community was enraged at the atrocities perpetrated by the Armenians and protested at their brutality. The commission’s report said that during the March massacre Russians, Jews and Georgians did their best to rescue Azerbaijanis. (See Azerbaijan Republic State Archives on Political Parties and Social Movements (ARSAPPSM, f 277, list 2, file 16, p. 18)

On 2 April, an Armenian officer accompanied by three soldiers went along the back street between the building of Kaspi newspaper and the Ismailiyye, the Muslim Charitable Society, and entered the society building. Soon after, fire and smoke billowed through the windows and the building, the pride not only of Azerbaijanis but of the whole city, was ablaze.

A young man who survived the massacre, Mahammad Muradzade, wrote an account of the atrocity in a booklet published in 1919 Mart hadiseyi alime. (The booklet was republished in 1996 by the Azerneshr printing house). Muradzade wrote: “I won’t forget the night of Monday 19 March [1 April] as long as I live. That night our family was sure that we would not see one another the next day, but would join eternity.” (M. Muradzade, Mart hadiseyi-alime Baku, 1996, p. 11)

The report by the chairman of the investigation commission said that despite the truce between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis, Armenians regularly killed Azerbaijanis in the streets of Baku, throwing their bodies into wells or the sea, until 15 September when Azerbaijani and Turkish soldiers liberated Baku. (See ARSAPPSM. f 277, list 2, file 16, p. 18)

Shaumyan paints slaughter as struggle for Soviet power

On 13 April 1918 in a letter to the Soviet of Peoples’ Commissars in Moscow Stepan Shaumyan attempted to give a political context to the March attacks by Armenians on Azerbaijanis. He claimed that the attacks were the result of the Armenians’ loyalty to the Soviet government and not of their national prejudice. Shaumyan wrote: “The Soviet Red Army – our international red army – and the Red Fleet, which we built in a short period and Armenian national divisions, were fighting the Muslim Wild Division, led by the Musavat Party, and armed Muslim gangs.” (Stepan Shaumyan, Selection, II part B. 1978, p. 259)

This brief quotation shows how Shaumyan concealed his Armenian nationalist Dashnak nature in the cloak of Bolshevism, describing the slaughter of Azerbaijanis as a struggle for Soviet government.

In his letter, he described his people as “real doves of peace”, and the Azerbaijanis as “butchers”. This is real hypocrisy and deception.

In fact, the Muslims did not have any armed forces or weapons. Those whom Shaumyan described as fighters of Soviet armed divisions were in fact Armenian Dashnaks and nationalists pretending to be Bolsheviks.

Shaumyan boasted about the Armenian brutality against Azerbaijanis: “We have gained brilliant results in the battles. The enemy has been utterly annihilated. We forced conditions on them and they signed them.” (Shaumyan, op.cit., II part, pp. 259-260)

Socialist Shaumyan shamelessly justified the involvement of the armed forces of the Dashnaksutyun Party in the slaughter of Azerbaijanis in Baku. He wrote in his letter to Moscow: “The presence of national divisions has partly characterized the civil war as a national massacre, but it was impossible to do otherwise. We did it on purpose. Poor Muslim people have suffered a great deal, but have now come together with the Bolsheviks and Soviets.” (S. Shaumyan, op.cit. p. 260)

The letter reveals some interesting information. Shaumyan wrote that units of Red Guards including Armenian, Muslim and Russian workers defended the oil fields from attack from nearby Muslim villages. Soviet soldiers of other nationalities were driven away by Shaumyan under the pretext of defending the oilfields and the city.

Azerbaijani death toll reaches 15,000

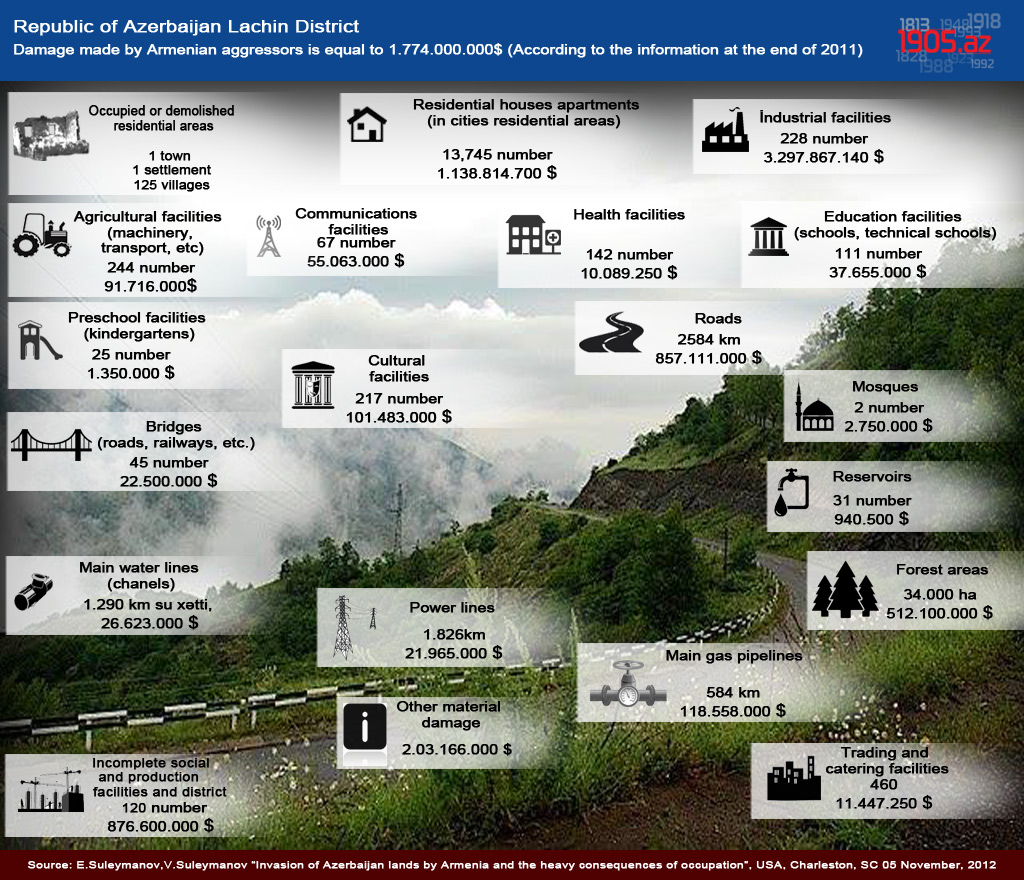

Our archives have preserved many protocols from investigations, documents on the looting of various houses and streets, murders and massacres, testimonies from eyewitnesses and victims, reports on damage to different families, death tolls and lists of the wounded, which were com-piled by the Extraordinary Investigation Commission into the Baku tragedy. (See ARSAPPSM, f. 227, list 2, file 13-16, pp. 25-26)

Unfortunately, the Commission was unable to complete its investigation into the number of dead and wounded and the scale of the damage. Shaumyan wrote in his letter to Moscow that 3,000 people had allegedly been killed on both sides. (See S. Shaumyan, op.cit., part II, p. 259)

However, the documents that have been preserved and the photographic evidence of destruction on a massive scale prove that 15,000 Azerbaijanis were killed and tens of thousands wounded. Losses in property ran into millions.

Stepan Shaumyan and other prominent Armenians took the lead in the March massacre.

National mourning

The anniversaries of the massacre committed by Armenians against our people were marked on 31 March in both 1919 and 1920 as a national day of mourning. However, the Soviet government attempted to make Azerbaijanis forget the tragedy. Soviet historians said that the March events were not a genocidal policy of one nation against another, but part of the Russia-wide civil war, the struggle of the Bolsheviks for Soviet power and their victory against anti-revolutionary forces. However, despite the attempts of the Communist ideologues, the Azerbaijanis have never forgotten the bloody events of March 1918.

Once the Bolsheviks had established their authority in Azerbaijan, the democratic Azerbaijani intelligentsia, who had been forced into exile abroad, marked the date as a national day of mourning, and published newspapers and memoirs about the tragedy.

The 31st issue of the newspaper Istiqlal edited by Mammed-Amin Rasulzadeh, leader of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and published on 1 April 1933 in Munich, was completely dedicated to the 15th anniversary of the tragedy. “National music, dance, joy were shaking the Ismailiyye building on 22 March 1918 in Baku,” Istiqlal wrote. The Novruz holiday was being celebrated. Little more than a week later this historic building, which housed Azerbaijan’s political, scientific, literary, economic and public unions, as well as libraries, press halls and an orphanage, was on fire. It was not only the Ismailiyye that was burnt out, but also all publishing houses, media offices; national theatre buildings, schools, hospitals, mosques and cultural institutions belonging to Azerbaijani Turks were badly damaged. Baku had changed its facade within just one week.

Prof. Atakhan Pashayev

Visions of Azerbaijan. -M2.2 Spring.-2007.-P.32-36

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO

Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO

Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO