According to a UNESCO decision, the Mugham of Azerbaijan has been proclaimed a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. In Azerbaijan proper, where the Mugham is perceived as an integral part of a system of fundamental cultural values of the Azerbaijani people, this decision is viewed both as a recognition of the merits by outstanding representatives of the genre and as a desire to attract the attention of the world’s cultural community to this unique heritage.

Possessing a centuries-long history, the Mugham reached its heyday in a period described by specialists as Eastern Renaissance, when, on a foundation of Greek-Roman heritage, the Azerbaijani culture created masterpieces in different spheres ranging from literature to architecture. The subsequent development of the Mugham did not alter its essence and importance. The Mugham continues to be a cultural microcosm which, on the one hand, is a heritage of the past and, on the other, a very modern art. Its strict canonic requirements harmoniously blend with the possibility of improvisation and creative development of the theme.

The unique Mugham culture evolved on a rich philosophical, musical and literary foundation. Those performing the Mugham are often perceived by listeners as carriers of an archaic magical code passed on from one generation to another. This provides listeners with the opportunity to connect to the eternal truth and obtain peace of mind.

No academic books are capable of communicating the nuances of this art’s living tissue. The Mugham performers, as people initiated into a mystery, can demonstrate this evergreen tree of living music and poetry through every performance. As a synthetic art, Mugham is based on classical Azerbaijani poetry which is full of allegories and symbols. Aesopian is combined with a mystical sense. The context of every poetic line, its real meaning opens only to those knowing eastern philosophy, the language of symbols and circumlocutions, can decipher the hidden implication of certain lines. From their early years, the Mugham performers develop an infatuation with the form of versification widely used in the writing of ghazels. No Mugham performer will tell you how many ghazels of different poets he knows by heart, but when it is necessary to reflect on a subject, the relevant lines will be remembered.

The Mugham was and still is an inexhaustible source of inspiration for Azerbaijani composers. The symphonic Mugham, created on the basis of classical music, is performed with tremendous success by orchestras in many countries around the world. At the same time, the Mugham is still a boundless source of exploration and interpretation for modern composers. Those knowing the Mugham well can “capture” it in different compositions which may initially appear to be quite far from it.

The Mugham intended for both solo performance and instrumental accompaniment is widespread in Azerbaijan. The bands performing the instrumental Mugham may have a different composition, but they are usually bigger than those meant for accompaniment only. Diverse and rich as instrumental Mugham is, it is the solo performance that is considered an apogee. It is in the solo performance that the listener can pick up the Sufi mysticism of a “journey into the astral plane” which, according to the connoisseurs of Mugham, forms the essence of such musical meditation.

The Mugham singers are traditionally called khanende in Azerbaijan. Khanende usually sing to musical accompaniment. The band of musicians playing the national instruments may vary from a trio (tar, kamancha and def) to a whole orchestra.

There are several recognized schools of Mugham singers in Azerbaijan. Although this genre is widespread throughout the country, the centers that have given rise to separate schools of Mugham are Baku, Shemakha, Ganja, Nakhchivan and Shusha. The so-called Karabakh School of Mugham, which represents particular interest, developed mainly in Shusha.

First records of the Azerbaijani Mugham appeared in 1902. Sound recording of the Azerbaijani Mugham was pioneered by English “Gramophone”, German “Sportrecord” and French “Pate Records” companies. In 1913, the companies started establishing representative offices in Riga, Moscow, Warsaw, Petersburg, Kiev, Tbilisi and Baku. The Azerbaijani Mugham was also recorded by Russian “Concert-record”, “Monarch-record”, “Extraphone”, “Gramophone-record” and Hungarian “Premier-record” companies. A number of valuable records were released in Soviet times by the Aprelevka and the Nogin sound production factories.

Most of these records are stored at the Azerbaijan State Archive of Audio Records. Some are kept at the Azerbaijan State Museum of Musical Culture. Certain old records of Azerbaijani Mugham are also stored at sound archives of the British library. A lot has been done in Azerbaijan to restore old records. For instance, early 20th century records have been converted into a digital format. They had not been circulated before, were recorded in one copy and were not intended for dissemination.

The political cataclysms brought about by World War One, the breakup of the Russian empire and the establishment of the Soviet Union led to a deep crisis of the Mugham as a genre. Soviet ideology viewed it as a superannuated art alien to the proletariat. Even the tar, leading instrument of a Mugham performance, could not avoid attacks. Despite being driven underground, the Mugham managed to return to official cultural life. But first high-class studio records of Mugham masters from the Karabakh School were only made in the 1930-50s. These records bear the voices of Khan Shushinskiy, Zulfi Adigezalov, Seyid Shushinskiy, Abulfat Aliyev, Mutallim Mutallimov, Yagub Mamedov, Islam Rzayev, Arif Babayev, Murshud Mamedov, Gadir Rustamov, Suleyman Abdullayev.

Finally, the third group of performers earned recognition in the late 20th century. It is represented by such khanende as Vahid Abdullayev, Sakhavet Mamedov, Zahid Guliyev, Garakhan Behbudov, Mansum Ibrahimov, Sabir Abdullayev, Fehruz Mamedov.

It is said that people should prepare for the birth of a great talent for centuries. By the time a talent is born, there must be lullabies he will hear, fairy tales that will teach him how to distinguish the good from the bad, and songs that will initiate him into the heritage of his ancestors. One thing is obvious – if people and the environment surrounding a talented person are not ready to perceive him, he may end up not realizing himself and remaining unclaimed. From this standpoint, Karabakh khanende were lucky to be born in a place and at a time when the environment was ready to embrace them.

Their birth in Karabakh largely predetermined their fate. They were born in a place where almost everyone could sing and appreciate good voice and musical talent. Every native of Karabakh, whether born in the upper or lower parts of it, Shusha or Agdam, was a connoisseur of the Mugham and who could sing any folk tune.

The Mugham is believed to be molding human soul. In Karabakh, this was an interlocking process – the nature shaped souls that were highly receptive to everything beautiful, including music. The beauty and harmony of these places are reflected in the unique musical culture which had been cultivated by all performers from Karabakh for years.

Most of Karabakh khanende were born in Shusha. The Shusha theme, its image of an unassailable fortress and spiritual citadel, a cultural shrine of Azerbaijani people, will always be the leading motif of their work.

Every native of Shusha knew its history. But this knowledge wasn’t gained only from chronicles. The numerous “Stories of Karabakh” – the Karabakhname – were not seen only as handwritten tomes. They were an integral part of their present and past lives. Many historical episodes described in them were always retold, being passed from one generation to another. Thus, even minute details of historical events were preserved. The Karabakhname were a living history reflected in everyday life, architectural monuments, a reality in which historical truth of days bygone and the present harmoniously complemented each other. The history and nature of these places generated one of the main themes of the Karabakh School of Mugham – Karabakh. The well-known Mugham “Karabakh shikestesi” was and still is a visiting card of singers from Karabakh.

Shusha has given the world a multitude of musicians many of which chose the pen-name of Shushinskiy entirely in keeping with Russian poet Yesenin’s well-known phrase: “If not a poet, then not from Shiraz, if not a singer, then not from Shusha”. Shusha has given the world so many remarkable singers, composers and musicians that they could make up an encyclopedia of performing art.

Shusha has always been rightfully considered the musical conservatory of the East. People would come here from everywhere to listen to well-known singers and learn singing. But the city was famous not only for its musicians. The Shusha phenomenon represented a combination of unique natural factors and deeds of local people. So many remarkable people of different backgrounds were born in this city and produced the yet unseen music with the instruments they made, in the halls they built and on the wonderful poems they wrote. The atmosphere of this city is reflected in Alexander Dumas’ book about a journey to the Caucasus. It provides an impressive description of poetess Natavan from Karabakh.

The pure and crystal clear springs have earned Shusha a special reputation. The best-known of them, Isa Bulag, was seen by many as a symbol of Shusha. The mountains, which seem to be pointed right into the firmament, surround the amazingly beautiful plateau to create a unique outdoor music hall with incredible acoustics. The Jidir Duzu plateau has seen many a well-known singer. Ubiquitous Shusha boys “played pranks” with this natural miracle as their clear voices, only beginning to conceive the Mugham, could be heard flowing from different mountain passes and resonating against mountains. This unique polyphony, amplified by the murmur of springs and rustle of trees and backed up by a choir of birds, could only be created by children’s fantasy.

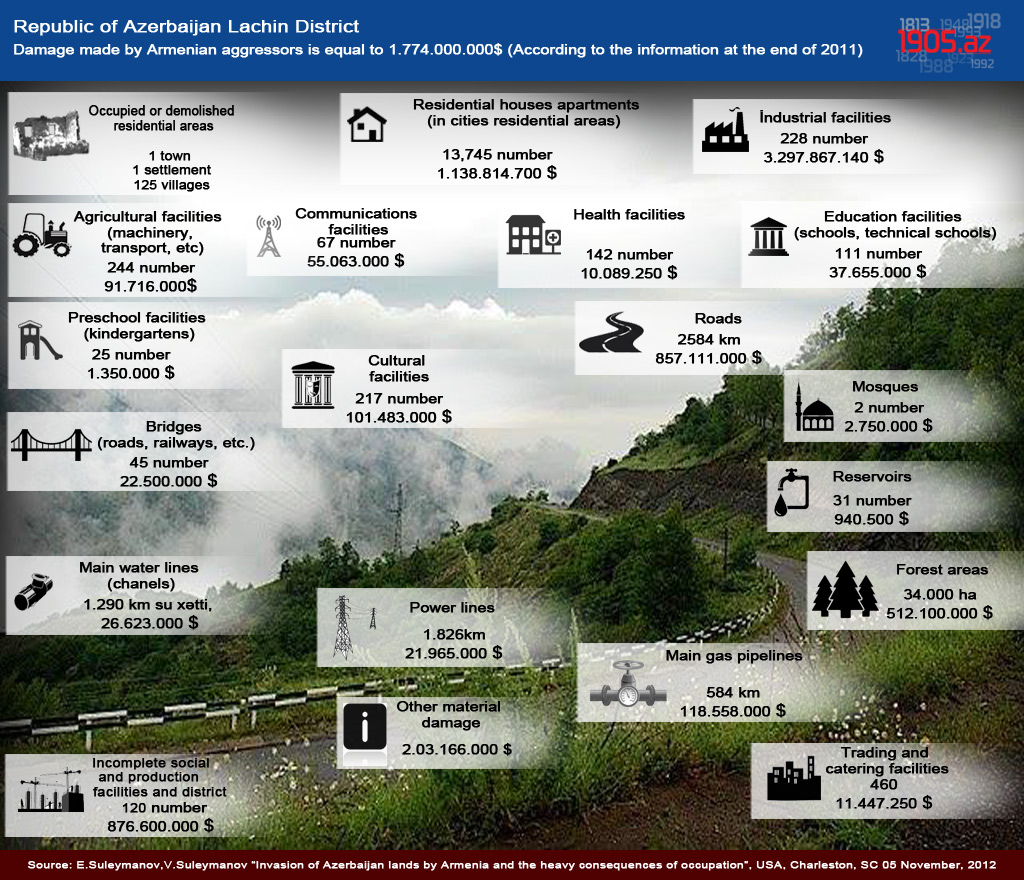

In 1987, the Kharibulbul international Mugham festival was held here. It was named after a flower growing in these mountains. What a constellation of young talents that festival revealed! The occupation of Shusha by Armenian aggressors in 1992 turned all these rising stars of Mugham into refugees. Now living in refugee camps, they sadly admit that they haven’t sung since the days of expulsion. “We, people of the mountains, can’t live and sing in a valley. Our souls are there in Shusha. How can we sing without mountain springs, without the clear mountain air, without the chatter of birds of Jidir Duzu?” Is there an answer? One can only wince in helplessness at the depth with which these kids perceive the world.

According to unwritten laws, there were several classes of musical gatherings in Shusha. First were the majlises where elite musicians were invited. Songs based on previously unheard poems were particularly appreciated. As long as the quality was good, it didn’t matter whether the singer found a poem in an old manuscript or borrowed it from a modern poet. Dancing melodies were not played at such gatherings, while the Mugham was performed with all the nuances.

Less professional musicians were invited to second-class majlises. The Mugham was performed there too, but after two hours, a folk tune would be played and people would be allowed to dance. Third-class majlises brought together those who wanted to have fun. They were not intended for serious music and the khanende respecting themselves would usually avoid them.

Although such classification was rather conditional, it helped firstclass musicians to maintain a high level of performance for many years. The same applied to listeners. In essence, the gatherings of real connoisseurs of the Mugham caused the genre to develop and be an ever-living form of folk art.

Writer Abdurahim Hagverdiyev said that whatever musician you might meet in the latter half of the 19th century in Baku, Shemakha, Ashkhabad, Tehran or Istanbul, some would surely be from Shusha. They were the ones shaping the musical fashion in the East, and people interested in having their voice and talent assessed would always go to Shusha. Years later, having become recognized khanende, they would cite an assessment they received from Haji Huseyn, Sadikhjan, Mirza Mukhtar, Jabbar Garyagdioglu or other masters of the Karabakh Mugham.

The first oil boom in Azerbaijan took a toll on the development of the Mugham art. The Eastern Parties organized by Baku’s oil industrialists were a tremendous success. The first of them were conducted at the Shusha theater. It was with the Eastern Parties that the transformation of traditional musical gatherings of Mugham connoisseurs into public concerts began.

Over the 20th century, the Karabakh School of Mugham gave the musical world many remarkable musicians. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict disrupted the continuity in the preparation of khanende. There is a saying that the muse is mute when guns do the talking. The Karabakh khanende are not mute, they do sing, but their singing is full of pain, grief and suffering. As Great Jabbar Garyagdioglu said, “Even if I were in paradise, what would it be worth without Karabakh.”

Different changes are taking place in this rapidly globalizing world. The human traffic unseen ever before, the possibility of almost instantaneous transmission of information, new technologies changing the appearance of the world – all this is taking place against the backdrop of growing threats of terrorism and natural calamities. In a world so vulnerable to these impacts, a human being is as small as a grain. Neither the globalization nor anti-globalization philosophies can return him the lost harmony. But this is the time when we must lay a foundation for our future development which is closely intertwined with the Tradition. Only by preserving the Tradition of each civilization and the culture of every people can we reach cultural diversity, a world where the Tradition can be protected and enriched. These are the goals of the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Mehriban Aliyeva,

UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador,

President, Heydar Aliyev Foundation

Journal “Irs-Heritage”, No 3, 2012, p.26-32

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO

Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO

Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO