The absurd statement by the Armenian president that the population of Karabakh was allegedly “homogeneously Armenian” for millennia and that “Turkic-Muslim nomadic tribes began to settle here only in the second half of 18th century, and their number at the beginning of the last century was barely 5 per cent of the total population” has absolutely nothing to do with science or historical fact. To be more convincing, Sargsyan referred to mysterious “Turkish official sources of the 18th century”. Of course, there was no further clarification as to what sources the author of this unscientific nonsense had in mind, as there are no such sources behind the walls of the Armenian laboratories of historical falsification. The Turkish archives, in fact, suggest the opposite. In November 2009, the Central Department of the State Archives under the Turkish Cabinet of Ministers issued a 660-page book called “Karabakh in Ottoman Documents” based on archive materials. The book consists of two parts – “Political, Military and Diplomatic Relations” and “Resettlement”, which, based on archive documents, cite evidence of the resettlement of Armenians to Karabakh. Ottoman archives have no mention of Armenians in Karabakh, and all documents indicate that Armenians settled in Karabakh from the 17th-19th centuries and changed the ethnic composition of the population.

Sargsyan’s “discovery”, to put it mildly, does not really match what Armenian historians themselves write. For example, George Bournoutian notes: “A number of Armenian historians, referring to statistics since the 1830s, incorrectly assess the number of Armenians in Eastern Armenia under Persian rule, giving a figure of 30 to 50 per cent of the total population {Serzh Sargsyan put the number of Armenians at 95 per cent of the total population!} In fact, according to official statistics, after the Russian conquest, the Armenians hardly comprised 20 per cent of the total population of Eastern Armenia, while Muslims made up more than 80 per cent. In any case, before the Russian conquest, the Armenians here had never been in the majority. Despite the fact that the Office Description indicates an Armenian majority in several mahals of Eastern Armenia, this change took place after the emigration of more than 35,000 Muslims from the region. Thus, there is no evidence of an Armenian majority in any district during the Persian administration. Perhaps the only place where the Armenians constituted a majority at a local level was Karbibasar mahal, in which the Armenian spiritual centre Uch-Kilsa (Echmiadzin) was situated. With the departure of thousands of Muslims and the arrival here of 57,000 Armenian immigrants from Persia and the Ottoman Empire, the Christian population had grown significantly by 1832 and equalled that of the Muslims. Yet only after the Russian-Turkish wars of 1855-56 and 1877-78, which resulted in even more Armenians coming to the region from the Ottoman Empire, and even more Muslims leaving the area, did the Armenians finally achieve a majority here. And even after that, until the beginning of the 20th century the city of Iravan remained predominantly Muslim.”

Citing statistical evidence according to which the number of Muslims in the Iravan and Nakhichevan khanates dropped by almost a third between 1826 and 1832 while the number of Armenians increased by 3.5 times due to immigration, Bournoutian notes further: “As is evident from the statistics, prior to the Russian conquest, the Armenians constituted about 20 per cent of the total population of Eastern Armenia and Muslims – 80 per cent. After the Russian annexation, 57,000 Armenian immigrants arrived here from Persia and the Ottoman Empire, while 35,000 Muslims fled Eastern Armenia. By 1832, the Armenians made up half of the total population.”

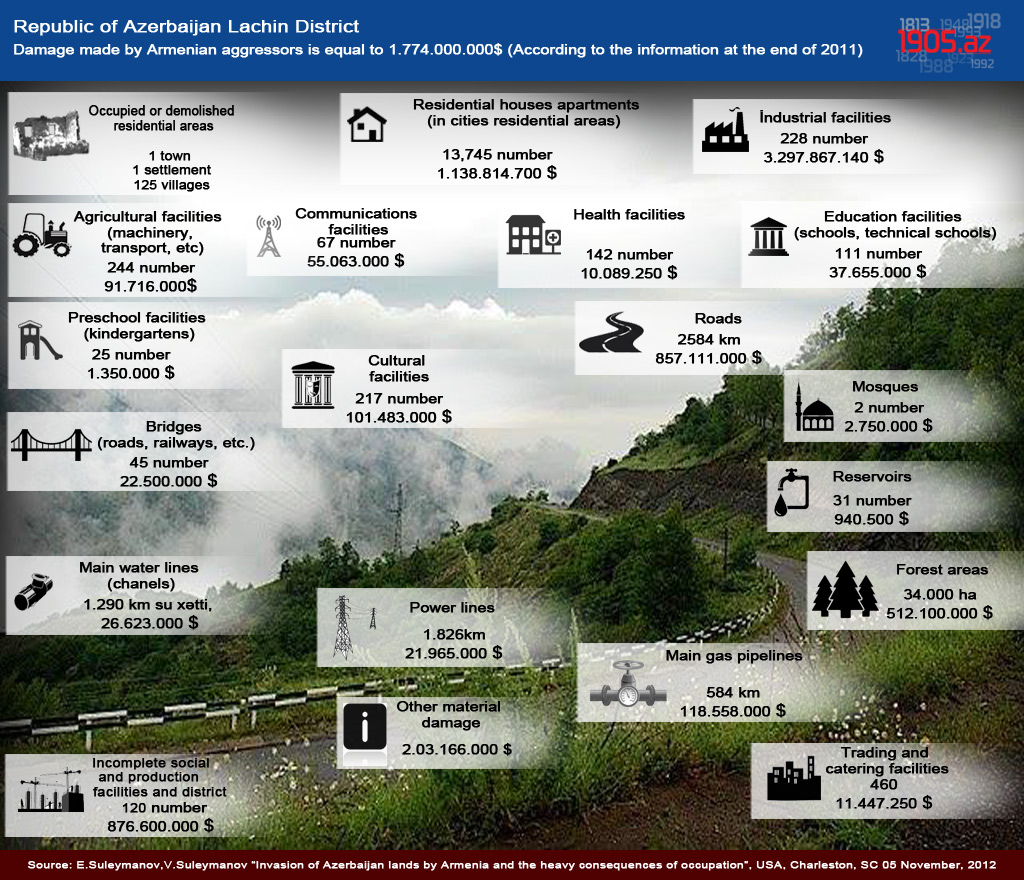

Prior to the conclusion of the Turkmanchay Treaty, there were even fewer Armenians in the Karabakh khanate, according to Russian statistics. “According to a Russian census, in 1823 Armenians comprised 9 per cent of the total population of Karabakh (the remaining 91 per cent were registered as Muslims), in 1832 – 35 per cent, and in 1880 they had already achieved a majority – 53 per cent,” says the Swedish author Svante Cornell.

After the conclusion of the Turkmanchay Treaty in 1828, Armenians began migrating en masse from Persia and the eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire to Iravan, Nakhichevan and Karabakh. The operation was headed by the Russian diplomat and poet, Aleksandr Griboyedov, who wrote in his “Notes on the Resettlement of Armenians from Persia to Our Regions”: “Armenians are mostly settled on the lands of Muslim landlords. In summer, it was still acceptable. Most of the Muslims landowners were away and had little opportunity to communicate with the heterodox incomers.” Griboyedov also warned about possible future conflicts between the Armenian incomers and local Muslims (as seen from the Office Description statistics, Muslims were mostly Turks, i.e. Azerbaijanis): “He (Prince Argutinsky) and I also talked a lot about the need to persuade Muslims to reconcile with their present burden, which will not be long, and eradicate their fears that the Armenians will take over forever the lands where they were allowed for the first time!”

The resettlement of Armenians to Karabakh, Iravan and Nakhichevan was described in detail by the Russian writer and historian, S.N. Glinka, in “The Description of the Resettlement of Azerbaijani Armenians to Russian Territory with a Brief Preliminary Statement of Historical Times of Armenia”, published in Moscow in 1831. From 26 February to 11 June 1828, i.e. within three and a half months, 8,249 Armenian families, or at least 40,000 Armenians, were resettled here from Persia. In the next few years, another 90,000 Armenians were resettled to these three former khanates of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1911, another Russian writer, N. Shavrov, wrote: “Of the 1.3 million Armenians currently living in the South Caucasus, more than one million are not indigenous, and were resettled by us.” “The Armenians were settled mainly in the fertile lands of Yelizavetpol and Erivan provinces where their number was negligible. The mountainous part of Yelizavetpol Province (Nagorno-Karabakh) and the shores of Lake Goycha were populated by these Armenians.”

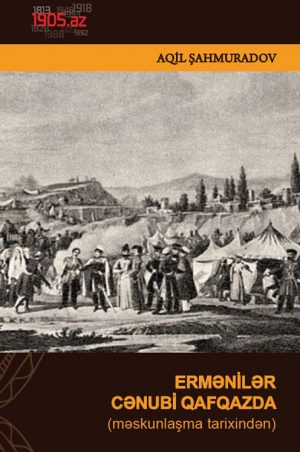

The historical fact of the resettlement of Armenians to Karabakh, Iravan and Nakhichevan is reflected even in the works of artists, in particular, in a picture which was drawn by the famous Russian artist Vladimir Mashkov in 1828 and clearly reflects the theme of the mass migration of Armenians from Persia to the northern bank of the Araz River.

From Ramiz Mehdiyev’s book titled “GORUS-2010: Season of theatre of the absurd”. (Kiev -2012)

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held

Inauguration ceremony of President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was held Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO

Ilham Aliyev wins presidential election with 92.05 percent of votes VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev, First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members voted in Khankendi VIDEO Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO

Plenary session of 6th Summit of Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia gets underway in Astana. President Ilham Aliyev attends the plenary session VIDEO President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO

President Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Azerbaijani TV channels in Prague VIDEO